The “Calculus of English”

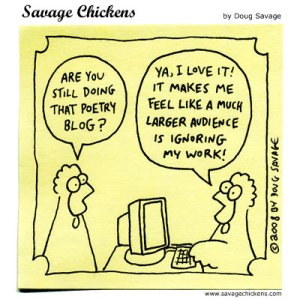

One of my students said something fascinating on Friday. He compared poetry to calculus. He said, “You know, Ms. Shea, I feel like poetry is the calculus of English. Not everybody is forced to take calculus in high school if they don’t want to, but for some reason everybody is forced to read poetry.”

The guy has a point.

I disagree with him on a fundamental level–I believe poetry is much more like art, like painting, than it is like calculus. One of the things that tends to bother some people about poetry is that there is no one right answer to it–it resists computation and calculation and most things left-brain related.

But you can see where he is coming from. He said, “Poetry is for the elite.” And to be honest, some poetry definitely comes off that way. And sometimes the way we teach it makes it seem that way.

Why, I wonder?

I alluded in my last post to not analyzing poems with students. This seems to be rather the opposite of what most English teachers do (and what I myself have done), and especially the opposite of what AP Literature teachers are supposed to do–but I think it is very important. And I also think it is important to explain to them explicitly that we are not going to analyze poetry today. I am not going to ask you today what you think X poem means. Eventually, I want them to be able to do analyze in a certain sense, but not right off the bat, not in the way they expect.

But this non-analytical approach is not unique to poetry.

Think about it. People spend their lives analyzing baseball–tracking players and teams, predicting outcomes, developing detailed spreadsheets to keep track of every single pitch. And they love it! But a Dad does not introduce his kid to baseball by sitting him down and explaining how stats work and what an ERA means and how to determine what your options are when you’re a left handed pitcher with a right-handed powerhouse at bat with the bases loaded.

No — he takes his child outside and plays catch with him. He teaches him how to throw a ball. And they have fun.

Or take another example that doesn’t involve any math.

If you’re someone who loves Bob Dylan songs and you want your boyfriend to understand the stark beauty of that scratchy voice, you don’t break down the lyrical allusions or explain the folk heritage influences. You put on your favorite Bob Dylan song and turn the volume up. Or you learn the song and play it and sing it with your own lovely voice– because surely he will be able to appreciate that.

If you want a friend to love Vietnamese food and she has never tried it before, you don’t describe all the ingredients or compare and contrast the flavor palette with Panda Express. You make her (or take her to a restaurant that serves) bot chien and pour her a glass of wine.

We must find ways to help our students experience and savor the beauty of something before we challenge them to “learn” it.

The word “analysis” (Grk: ᾰ̓νᾰ́λῠσῐς) means to unravel, to take apart, piece by piece, so that you can (presumably) come to a better understanding of it. But most things, when you take them apart too much, just stop working altogether. Like a human being, for instance.

A really good doctor should have a sense of the human being as a whole before she starts investigating the individual parts and organs. A man does not fall in love with a woman’s eyes, but with a particular woman. He notices her eyes, to be sure–but only insofar as they suggest the mysterious integrity of her person.

I am finally realizing that this is true of everything I teach, but most especially of poetry. How can you properly learn anything unless you have some kind of genuine love for it? Some simple awe and curiosity?

But I am still figuring out how. How do I impart that?

For my first full-on poetry lesson with my AP students (I know, I know, I really should have started earlier this year)– I gave them a packet of pretty accessible and short poems. Billy Collins, Naomi Shihab Nye, Gwendolyn Brooks, Richard Wilbur (of course), a war poem, a Shakespeare sonnet (116 for the kids who loved watching “Sense and Sensibility”), a poem about rain, “Poetry” by Marianne Moore (“I, too, dislike it”), “The Questions Poems Ask,” … Anyway. Their homework was to read all these poems at least once and pick one they liked OR that they “didn’t hate” (since that more accurately described some of the super smart boys’ feelings). They were not allowed to annotate or analyze them.

“Remember–no analyzing! No annotating!” I said to them, smiling as they walked out my door. “Okay, Ms. Shea.”

When they came back to class two days later, I had them spend some “non-analytic” time with their poems. They copied the poems down by hand, line by line. (There were some grumbles at this about “busy work”— but then one girl realized that she hadn’t even noticed that the poem rhymed until she copied it down, and another student said “oh— every line ends with the word ‘rain'” and another student was like “whoah there are a lot of semicolons in this…” so I think they understood for the most part that it can be a good thing to just slow down with a poem and follow the poet’s thinking.) Then they chose their favorite image from their poem and had to draw it as literally as possible. I was particularly encouraging and stingy about this.

“I like how you drew your clouds in front of the sun instead of behind it. But how are you going to convey that the sun comes up ‘not in spite of rain / or clouds but because of them” in your picture?”

“I like your little guy waving on the shore, but how are you going to show that the other person is waterskiing ‘across the surface of the poem’, not across the surface of water?” (This student wrote the word “poem” and drew an arrow to point at the water.)

“That line has a ‘you’ in it. How are you going to show the ‘you’ in your picture?”

They huffed and puffed, but even as seniors in an AP Lit class most of them seemed to like the challenge of drawing and noticing.

I’m planning on having them recording themselves reading their poems out loud on their phones. Yes– they will be using technology–but last year, when I assigned this task as homework to my sophomores, those kids ended up recording themselves multiple times because they kept skipping words or pausing in awkward places. In fact, some of them re-recorded themselves so often that they memorized huge parts of their poems without realizing it.

Ah, yes. Exactly.

So, even as I try to model for my kids how to approach a poem humbly and carefully, without trying to tear it apart or lose the joy in reading it, I hope I can continue to just read poems aloud to them and find other ways for them to experience these works in their uniqueness and beauty.

As I tried to point out to them on Friday, even noticing “positive” and “negative” tones is something they do all the time with their friends in conversation. We are always picking up on the facial cues of others—and even if we do not know exactly how someone else is feeling on the inside, we can make some good guesses that help us encounter that person more deeply.

Poems are like that.

If calculus is also like that somehow, I stand corrected.